If you’re a regular user of the terminal on a UNIX system, there are

probably a large number of behaviors you take mostly for granted

without really thinking about them. If you press ^C or ^Z it kills or stops the foreground program – unless it’s something like emacs or vim,

in which case it gets handled like a normal keystroke. When you ssh to

a remote host, though, they go to the processes on that machine, not

the ssh process. You probably know that your shell is using

libreadline (or something similar) to give you high quality line

editing and history, but who’s responsible for the (much poorer) line editing you

get when you’re typing to a cat process?

The answer to all these questions involves the unix terminal emulation layer, and the termios interface for interacting with asynchronous communication devices (such as serial ports connected to terminals, or their virtual equivalents). This blog post will be part 1 of what will probably be a three-part introduction to tty emulation and termios in unix (with a focus on Linux, since that’s what I know and use) and to the APIs for interacting with it, as a springboard to understanding how these layers all work and where these behaviors come from. Along the way, you’ll learn a bit more about customizing the behavior of these layers, which can come in handy both as a user, and if you write terminal-based applications for unix.

The terminal device 🔗︎

The primary abstraction that governs any interaction with a terminal

in Unix is a “terminal” device, or tty for short. In most cases these days, since you’re

not interacting with a physical terminal, you’ll be dealing with a “pseudo-terminal” (“pty” for

short – see pty(7)), which is a purely virtual construct. A

pseudo-terminal, simply, is a pair of endpoints (implemented as character devices in /dev/) that provide a bidirectional

communication channel. Whatever is written into one can be read out

the other, and vice versa. These two ends are known as the “master”

and “slave” ends. Unlike pipes or sockets, however, they don’t always pass data directly through. What makes terminal devices special is the layer that sits between the

master and slave, which can filter, transform, and act upon the streams in both directions.

In standard usage, the “master” pty is connected to your terminal

emulator (e.g. xterm), and the “slave” pty is connected to the

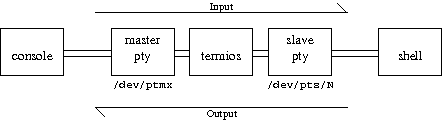

program being run (e.g. your shell). “Input” flows from the user into the master pty and out the slave, and “output” flows from your program into the slave and then out the master. The basic diagram for

what’s going on, then is:

This diagram is a simplification in a few ways, but it still captures most of what’s going on.

What happens in the middle? 🔗︎

That block I’ve labelled “termios” in the middle is responsible for essentially all of the behavior I listed in the first paragraph of this post. By default, it implements behavior including:

-

Line buffering – when characters come in the left, it holds on to them until it receives a newline, at which point they are all emitted out the right at once.

-

Echo – when a character comes in the left, in addition to being buffered or sent out the right, it is also sent back out the left. This is why you can see what you’re typing.

-

Line editing – When the

ERASEcharacter (^?, ASCII0x7fby default) comes in the left, assuming that there is anything in the input buffer, the last character in the input buffer is deleted, and the sequence"\b \b"is sent out the left."\b"(ASCII0x08) tells your terminal to move the cursor one column to the left, so this moves the cursor one column backwards, overwrites the last character with a blank space, and then moves the cursor back. -

Newline translation – if a newline (

"\n", ASCII0x0A) comes in the right, a carriage-return/line-feed combination (CRLF,"\r\n", ASCII0x0D 0x0A) is sent out the left. While most programs on UNIX accept a bare"\n"as a newline, your terminal needs both –"\r"tells it to move the cursor to the beginning of the line, and"\n"tells it to move to the next line. -

Signal generation – if a

INTR(^C, ASCII0x3by default) comes in the left, it is discarded and aSIGINTis sent to the program on the far right. Similarly, if aSUSP(^Z, ASCII0x1A) comes in the left, it is discarded and aSIGTSTPis sent to the program on the far right. (SIGTSTP, by default, stops a process. It differs fromSIGSTOPprimarily in that it can be caught and handled by a program, whereasSIGSTOP’s effect is unconditional)This is the source of at least two of the additional complications I mentioned to the basic diagram above:

- The “termios” block does not strictly sit in the middle of the diagram. It also knows about the program(s) all the way over on the right, and can interact with them in (certain) ways that aren’t just sending characters to the slave pty.

- There may be multiple programs connected to the slave

pty. Which one(s) should be allowed to actually read from it?

Which one(s) should

SIGINTorSIGTSTPgo to? The answers are fairly complicated, and I don’t claim to fully understand them, although I know some of the basic rules. I may write a future blog post once I understand them better.

There is even more that happens in that box, but these are the most noticeable ones, and selected to give you a feel of how the system works. Programs using the terminal can selectively enable or disable each of these features individually, as well as all the others I haven’t mentioned. In a future post, I will look at the interfaces we can use to control

what processing does and does not happen, as well as how new pty pairs are created and used.

If this all seems somewhat arbitrary or weirdly constructed to you – well, it pretty much is. It makes sense, however, in the context of when this interface was first invented. When the tty layer was first coined, your “terminal” was a physical terminal – perhaps a VT100 or its ilk. C was the state of the art for programming languages, code size was expensive and libraries barely existed. Putting logic into the left side of the picture meant upgrading a physical piece of hardware. Putting logic into the right side of the picture meant putting it into every program you might want to talk to on the right side – libreadline and shared libraries didn’t really exist yet. And so, the logic went into the only place it could – the kernel, which could sit between a dumb terminal and a dumb program and mediate just enough logic to let programmer correct their typos as they worked. The kernel already had to mediate the connection, since terminals were physical devices, and there already had to be interfaces to control this layer from software, since software needed to be able to change such details as the baud rate and presence of parity or stop bits to communicate with the terminals. And so this layer that was already sitting between user programs and the console grew additional intelligence a bit at a time. And once we had terminal emulators and virtual terminals, the whole layer moved along with them, as legacy interfaces are wont to do.

Next time: The termios(3) APIs.