The fundamental tool of any engineering discipline is the notion of abstraction. If we can build a set of useful, easily-described behaviors out of a complex system, we can build other systems on top of those pieces, without having to understand to worry about the full complexity of the underlying system. Without this notion of abstracting away complexity, we'd be stuck writing our webapps in assembly code – if not toggling them in to our frontpanels after painstakingly translating them into hex by hand.

One of the interesting things about computer security, which makes it both so difficult and so fascinating, is that it often doesn't obey abstraction boundaries. For the most part, security problems happen when abstractions are violated, and you leave the realm of behaviors that can be described in terms of your abstractions. One class of security problems are "spec bugs" – problems of the form "Oops, we forgot we needed authentication for that operation" – but the "interesting" ones, at least to me, are the ones where the security problem can't be fully understood in terms of the usual abstractions.

Here's one of my favorite examples. I've heard it claimed that the US actually used an attack of this sort against the KGB during the Cold War, but that may be apocryphal. I certainly haven't found a citation. The example is illustrative in any case.

One-Time Pads

Everyone knows that a one-time pad, used properly, provides perfect encryption. Given a message M and a randomly generated key K of the same length, we can compute C=M⊕K (that's an XOR), and as long as K is only ever used once, the ciphertext C is perfectly random and provides no information about M, no matter how sophisticated the attacker.

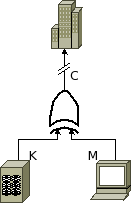

So, let's imagine, secure in that knowledge, we build a one-time pad encryption system. It looks something like this:

A key flows in off of some kind of key storage system, and an operator types in a message. These values flow in to an XOR gate, and we send the output of the gate down the wire off to our collaborators in another big building somewhere.

We use the system for months, being very careful about key management -- we generate keys based off of readings from a geiger counter pointed at a mildly radioactive source, and only ever using any given section of the pad once. All is well and good until, six months down the line, we discover Eve sitting somewhere between us and our allies, probes carefully spliced into our cable. Even more disconcertingly, we find a stack of printouts of every message we've ever sent across our communications line! We know that we've been utterly paranoid in distributing and protecting our keys, so there seems to only be one conclusion left: Eve has somehow broken our "perfect" encryption system!

So what went wrong?

Let's look at our XOR gate. We know it's an XOR gate, so it must have the following truth table:

| m | k | c |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

But there aren't actually mathematical logic values entering it -- this is a physical system, implemented on physical hardware, and there is something representing those logic values. We're using a digital logic system, and so we're representing those values with voltages, in the range 0-5v.

The fundamental abstraction of digital logic is the notion of the static discipline, which defines the range that input and output voltages of devices fall into. Ignoring noise margins for the moment, for a 5v system, we might stipulate that voltages under 2v represent a logical "zero", and voltages above 3v represent a logical "one". So, instead of the above table, we actually have the following behavior table for a legal XOR gate:

| m | k | c |

|---|---|---|

| <2v | <2v | <2v |

| <2v | >3v | >3v |

| >3v | <2v | >3v |

| >3v | >3v | <2v |

Pulling out our trusty oscilloscope and signal generator, we disconnect our own XOR gate, strap it to the test bench, and measure its response. And lo and behold, we discover the following result:

| m | k | c |

|---|---|---|

| <2v | <2v | 0.5v |

| <2v | >3v | 4v |

| >3v | <2v | 4.5v |

| >3v | >3v | 1v |

So all Eve has been doing is listening to our communication line with her own oscilloscope, and reading off voltages, and she can extract both M and K!

In conclusion

So what went wrong here? We assumed our attacker was using the same abstractions we were. Within the scope of our abstraction, our system was secure. The math tells us that a one-time pad using an XOR gate is perfectly secure, and within the abstraction of our static discipline, our gate was a correctly functioning XOR gate. But the problem was, Eve isn't constrained to use our abstractions. To analyze the security of our system, we can't just look at it in terms of the abstraction we model it using, but we have to consider the details of the actual implemention.

Abstraction layers are not a fundamental property of a system. They are lines that we agree to draw onto it to keep ourselves sane when designing complex systems. But they are only that, and no more. No one is required to respect those lines, and so we are forced to analyze the system as it really exists, without those nice lines drawn on it, if we want to make it secure.

This is also not to say that abstraction has no role in security, or in building secure systems requires working without abstractions. Far from it -- complexity is an enemy of security, and abstractions are a key tool to reducing complexity. But it just means that you have to be careful, and build your abstractions with security in mind. Cryptography, for example, starts with a set of primitives -- hash functions, public key encryption algorithms, and so on -- and builds from them some basic tools -- pseudo-random number generators, commitment schemes, etc. -- that can be used to design cryptographic protocols. But, as much as possible, such constructions are based around mathematical proofs of the security properties of the derived constructions, starting from the mathematically well-defined security properties of the primitives.

Also, while this is one of the cutest examples I know of, there are still many examples of this principle in pure computer science. My favorite in software is perhaps exploiting buffer overflows and other memory corruption issues in C. The behavior of the system, in terms of C's abstractions, is undefined once you overflow a buffer. And so, in order to exploit a buffer overflow, or understand how exploitation is possible, you have to look under that abstraction, and understand the underlying system. And defenses like stack cookies or ASLR are all about changing the underlying implementations to be harder to exploit in certain ways, while preserving the visible part of the abstraction. The arms race of exploitation techniques and memory protection techniques we've witnessed over the last decade or so is all about playing various games below the layer of the usual abstraction barriers.

Addendum

Probably no one has ever built an XOR gate as egregiously asymmetrical as the one I described above. But if we look at, e.g. the standard CMOS wiring of an XOR gate, we see that it is in fact asymmetrical, so it's totally conceivable that the output need not be perfectly symmetric with regard to the two inputs. Note also that my point is not at all that this problem is difficult to solve -- one could easily stick some buffers on the output of the XOR gate, or do any of a number of other things. But the point is that without understanding the details underneath the usual abstractions you work with, this problem isn't even conceivable, never mind solvable.